Cedar Leys

Mike Dring explores a fine but little-known house by Peter Womersley

Mike Dring is an architect, senior lecturer, MArch programme director and researcher at the Birmingham School of Architecture and Design. First published in the Twentieth Century Society’s C20 magazine. Republished here with their permission. The original article can be viewed here.

In the late 1960s, the RIBA Journal published a series of articles under the general title ‘Architects’ approach to architecture’. One of these was by Peter Womersley (1923-93), who is perhaps best known for his first house, Farnley Hey, in Huddersfield (1952-55, Grade II). His story, told in the May 1969 issue, is one of experiment and logical progression as well as intuition and good luck. He describes his early commissions as ‘apparently getting him nowhere’, and his game-changing appointment as architect for the University of Hull sports centre in 1961 as ‘an absolute fluke’ (maybe, he says, the client thought they were getting ‘the real Womersley’ – in other words, John Lewis Womersley, chief architect of Sheffield City Council in the 1950s).

“What a client does not like is usually a surer guide to what he really wants”.

Womersley was born in Newark in Nottinghamshire, but grew up in Yorkshire. It was, he says, seeing photographs of Frank Lloyd Wright’s house, Falling Water, that decided him on his career. He trained at the AA School after WWII, and one of his most vivid recollections of his student days was being employed for a time as a labourer on the Festival of Britain site: the contexts of dutiful service in post-war reconstruction, and architectural and technological innovation were frameworks for his practice. Farnley Hey, the timber-framed house built for his brother John, meant ‘going into private practice off the deep end, with no experience of site procedure, or running a job’. Having secured two further projects in the Scottish Borders, he set up a home and practice there in 1955, describing it as ‘a marvellous landscape to build houses in’. Until 1961 he worked on his own, firstly in ‘a gloomy cottage in the outback of the Lowlands’, and then in his own house. For five years, he says, the ‘office vehicle’ varied from Vespa to Lambretta.

“The only possible function of a tiny office in these days of monster firms is to experiment aesthetically”

(Image credit: Dr Richard Brook)

In the early years he worked mainly on houses in Scotland – including High Sunderland (1956-57, Category A) for the textile designer Bernat Klein – as well as a number of houses in England. ‘If your practice is a new one based on private houses you are vulnerable,’ he writes, ‘as there is an antipathy towards the modern house which does not apply to other buildings… the number of houses rejected almost equals the number put up, and the reason is always the same – “unsuitable for the environment”.’ Then, in 1961, he won a competition to build the County Offices in Roxburgh, and, with the major Hull sports centre job coming through around the same time, he set up a rather bigger office and began employing other architects.

It is revealing to string together some insights from Womersley’s self-analysis. ‘All my buildings start on graph paper,’ he writes, ‘a pad travels with me most places. Areas are easily worked out, and a discipline is imposed on the building… It is I suppose subtractive architecture: beginning with one simple volume and breaking it down… A model is the only fair way of showing the client what he is in for… The design works from the inside out… the elevations of any building I design come very late in the day… Detailing is something which grows out of each building, forming an organic skin… I always like to be reasonably honest about the expression of structure as the generator of appearance… Of the 12 or 13 houses I have built, over half are framed buildings, all but one in timber; the other five are what might be called block houses with loadbearing walls…’

“Really good architecture needs no explaining – it makes a completely convincing statement on its own in visual terms”

(Image credit: Womersley's home, The Rig, Gattonside in the Scottish Borders. Photo by James Colledge)

His own house was finished in 1957: ‘It is a very simple traditional load-bearing brick structure on a 3ft grid linked via a covered way and a courtyard to the drawing office… a typically Miesian open plan… The development [from his early houses] to a more three-dimensional approach was natural and gradual. More pronounced recessions and projections at Camberley; exposed concrete frames on a brick plinth at Stratford on Avon [i.e. Cedar Leys]; leading to a house at Bath [just completed at the time of writing]. I believe in “a fresh rebuilding of experience gained”. A home for an individual is a natural one-off…I prefer to design my own system, and each building evolves its own, both constructional and aesthetic… I cannot understand the architects who think that architecture can be created from standard details, or who appear to distrust originality.’

“I believe in personal involvement with a building, if it is to have any chance of being good”

‘Cedar Leys’ at Alveston near Stratford on Avon was built for local industrialist Alan Joseph and his wife Bobbie. It marked not only a move south but his first foray into reinforced concrete. He had been recommended to the Josephs by Tibor Reich, a Hungarian émigré and family friend who lived and worked nearby. Reich was a textile designer, and it’s possible that Bernat Klein had put in a good word. Bobbie Joseph recalls that Womersley took them to see one of his houses in Scotland (though which one is not clear), which she recalls as having a strong relationship to the landscape, but rather unhomely, with no furniture other than a sofa in the corner.

Cedar Leys was commissioned in 1961 and completed in 1964. It was built on parkland surrounding Alveston Leys (c.1827), an estate which had been partly sold for development. The designer and silversmith Robert Welch was a friend of the Josephs, and had built his home, ‘The White House’ here in 1962, naming his ‘Alveston’ cutlery range after the village.

“'Less is more’ is the battle-cry, but how long can you develop an intellectual ideal, if it has to get more ‘less’ all the time?”

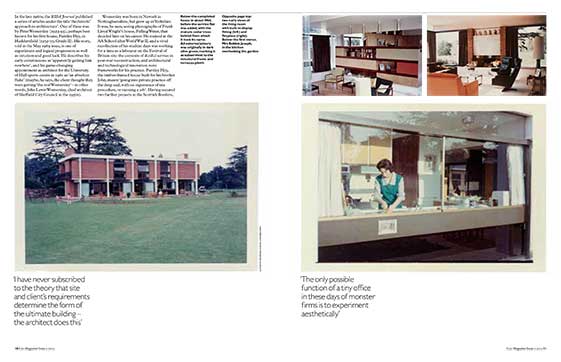

Womersley said that Cedar Leys was simply ‘exposed concrete frames on a brick plinth’, and its design recalls the geometrical neo-classicism of Philip Johnson at New Canaan and the Case Study Houses by Neutra, Eames and others. The primacy of structural form, and the breaking down of a simple volume through subtractive moves, frames and reveals the landscape as something to be surveyed and controlled, rather than directly engaged in. Indeed, Womersley originally intended the living accommodation to be on the first floor, close to the canopy of mature cedar trees and with elevated views over the landscape. The Josephs rejected this idea as impractical, as by the time the house was complete they had three children with another on the way.

“I have never subscribed to the theory that site and client’s requirements determine the form of the ultimate building – the architect does this”

Nonetheless, Womersley’s logic is consistently applied, the elevations offering a ‘faithful reflection’ of the inner planning through apparently floating panels of hand-made brick to the upper floor and a double-height glazed void to the entrance with adjacent (north-facing) reflection pool. The ground floor was entirely open to the landscape apart from the kitchen, where the sink overlooked the garden. Timber-framed glazing and a clerestory to the same depth as the cross beams emphasise the more contained upper floor.

(Reproduced with permission from the 20th Century Society)

All external joinery was originally in a dark olive green, a discreet contrast with the structural frame and terrazzo plinth used throughout the ground floor except in the recessed lounge area finished in maple strip (as he had used in his own home, The Rig). Womersley designed a built-in display fitting for to the lounge, the dining room was lined in pale limba wood panels and the entrance hall in mahogany.

Apart from the mention in the RIBA Journal, Cedar Leys was never published in the architectural press, apparently because Alan Joseph was fearful of exposing their house to burglars. But another reason could be that – although relations were good during commissioning and construction – Womersley was openly critical of the Josephs’ choice of furnishings (despite their use of textiles by Reich), and appalled by the addition of staff quarters to the east of the main building; according to Bobbie Joseph, he refused to speak to them afterwards. Although they only lived at Cedar Leys for four years, the Josephs enjoyed their time there, adapting the modernist framework to suit their family life until they decided they needed more space both inside and outside.

“I suppose the acid test for any architect is ‘Dare you keep visiting your buildings when they are occupied?”

The following years saw the house change hands three times, with each owner making their own style statement from patterned chintz to rustic villa. Although the building’s basic structure remained largely intact, significant changes took place in the service apartment, the reconfiguring of kitchen and entrance hall, and the loss of the master bedroom’s original bathroom and dressing room. Many of the high quality internal linings and fittings were replaced, and the terrazzo plinth was covered with cheap ceramic tiles. But the house’s fortunes changed for the better in 2011, when the house was purchased by Robert and Eleanor McLauchlan.

It’s not surprising that the McLauchlans felt at home at Cedar Leys; Eleanor’s father William Scrase was a volume house-builder of some repute, firstly in Staffordshire and later in Birmingham, and as a child she lived in St George's Close, Edgbaston, a development built by her father and designed by John Madin – the two men were close friends and business partners. After a spell in London, the McLauchlans and their young family moved in 1979 to another Madin-designed development at Westbourne Gardens in Edgbaston, where they remained for 25 years.

(Image credit: Dr Richard Brook)

Almost a year of work went into a comprehensive refurbishment of the house and grounds, drawing on Bobbie Joseph’s recollections, and the results are exceptional. Gone are the layers of unsympathetic materials and the inappropriate kitchen – indeed, the kitchen is perhaps an improvement on Womersley’s original layout, as it has been pulled away from the façade, introducing long views down the house which were not previously available. The concrete frame showed signs of steel reinforcement decay that needed specialist attention, and much of the south-facing window joinery and the first floor balconies had to be replaced. They have not attempted to recreate every detail, but have interpreted it to meet contemporary needs, and fifty years on the house still provides the delight that Womersley wished to create in all his works.