Giving delight

“Architecture is, as it were, petrified music”

Friedrich von Schelling, Philosophy of Art (1802-03)

‘My approach to architecture is relatively simple: I try and give delight,’ so wrote Peter Womersley. The architect arguably behind many of Scotland’s most notable 20th century structures, Brian Robertson hails his vision and delights in his buildings

Memory is always dangerous, but I think that I fell in love with the buildings of Peter Womersley long before I even knew what architecture was – deep down I just knew what was special and gave delight. I refer to his truly remarkable building at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh, the iconic Nuffield Transplantation Surgery Unit.

I was born in the Western General and spent my childhood years just a short distance away in a very simple square flat-roofed four-in-a block flat. (The building was a basic block concrete construction built to replace a bombed house. Unlike all the neighbouring houses it had a flat roof as no materials were available for a pitched roof – more of which later). I saw the strange and wonderful new hospital building by Womersley every week. To a young child in the late 1960’s this was a building from the space age, something from Gerry Anderson’s ‘Supermarionations’.

Great architects give us buildings that move and delight us, but their buildings are also completely functional. Here I seek to show you something of the magic of Peter Womersley through a very small sample of his buildings: the Nuffield at the Western General, the home and studio he built for the textile designer Bernat Klein outside Selkirk and the football stand he designed for a football club in nearby Galashiels. The views are biased and from an enthusiastic amateur rather than an expert (errors are all my own work). There is a real need and likely a great market for a definitive monograph on Womersley.

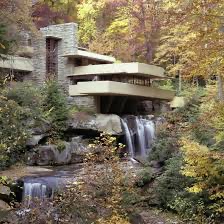

Peter Womersley (1923-1993) was born in Newark in Nottinghamshire. He declared he wanted to become an architect at school after seeing photographs of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater (1936-1939) built in rural Pennsylvania. He trained at the Bauhaus-influenced Architectural Association in London from 1947 to 1952. After graduating he designed his first house Farnley Hey, near Huddersfield, for his brother which won an RIBA Bronze Medal.

Womersley was a sole practitioner architect, only ever employing a maximum of four staff in the Scottish Borders from 1953 until 1978. The celebrated post- war architect, Sir Basil Spence when asked in 1960 to pick the best modern house in Britain replied, “anything designed by Peter Womersley”. Most of his buildings are in the Scottish Borders; sadly several are in a ruinous state either through decay and dereliction or insensitive additions. A superb home in Ayrshire, Port Murray House was scandalously demolished in 2016. There is reason for hope however as there is currently a resurgence of interest and investment in Womersley.

The Nuffield Transplantation Surgery Unit, Edinburgh designed 1963, built

1965 – 1968

“This building has been dismissed, I know, as a piece of sculpture, not architecture. I don’t see why a building should not be both.”

Womersley (1969)

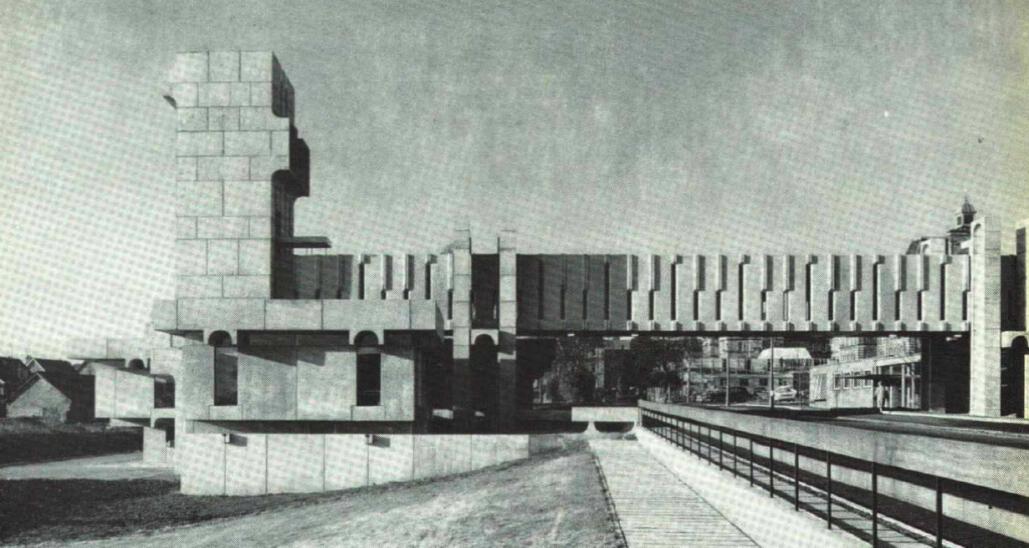

And there you have it, Womersley’s ethos, distilled. He spectacularly completed a very complex clinical brief and still achieved purely aesthetic ‘sculptural’ qualities. The Nuffield was the first purpose built organ transplantation unit in the world. It opened on 31 January 1968, just eight short years after the first successful kidney transplant in the UK, performed in Edinburgh by Sir Michael Woodruff and his team. Incredibly, by today’s standards, design began just over two years after this first transplant.

Woodruff and his colleagues realised that infection following surgery was the major cause of death in the early days of kidney transplantation. Patients had to be heavily dosed with immunosuppressants to prevent rejection of the donor organ, the downside being that infection was more likely. What was needed was effective isolation for the patients, with enclosed communication for radiotherapy, strict barrier nursing protocols, filtered ventilation and even windows guarded against the direct rays of the sun. Six completely isolated patient rooms were designed with two operating theatres, contained within a sterile unit, achieved through forced ventilation. Farsightedly, the clinicians also wanted “large picture windows where patients can see gardens, houses, people and children . . . and also see relatives or medical attendants in the visitors area.”

The Nuffield has been described as a strange, exotic, sculptured, ochre- coloured, fort-like concrete building. It has a basement plant unit partly hidden from the hospital access road by the sloping site. Inside the building has vaulted roof beams some which are carried through to the outside surfaces, including projections of ventilation inlets and outlets; these are purely aesthetic choices but give the whole structure a kind of lyrical ‘brutalism’. The windows and details seem like a piece of minimal musical composition. The tower gives the building a kind of bastion feel that is most clear at the bottom of the sloping site, below the road.

The honey colour of the external concrete is an unusual choice; it is warm and welcoming and incredibly striking in the Edinburgh sunshine – initially it was terracotta tinted concrete. The smooth finish of the concrete was achieved by using fibreglass lining in the formwork during construction, in marked contrast to the wooden shuttering Womersley used in several other public buildings.

The building has been modified over the years and is currently used as a day centre for cancer patients – organ transplantation is now much more routine. Womersley’s piece of functional sculpture does need a bit of tender loving care but it is sound – just a few years ago a double decker 113 bus ploughed into the bridgeway, ripping the top off the bus and injuring eight; the scrapes are still to be seen but this beauty still endures.

Gala Fairydean Football Stadium, Galashiels designed 1962, completed 1964

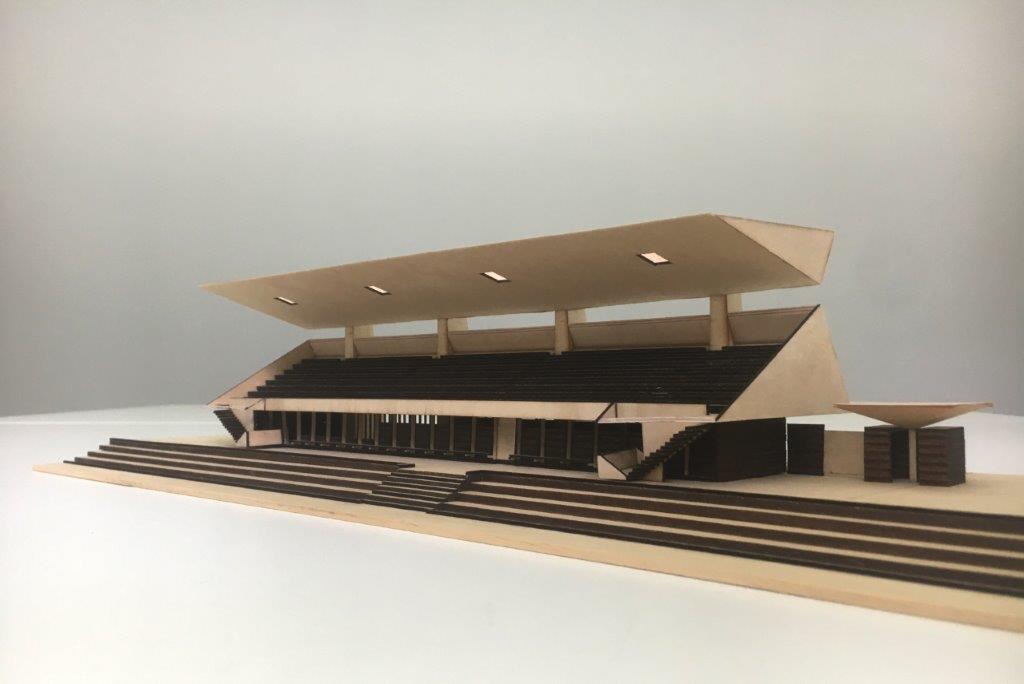

In the early 1960’s Galashiels in the Scottish Borders was a rich textile town with twenty-four mills and near full employment. The town also had a football lottery with a weekly first prize of a princely £100 (weekly wages in the mills were around £10); unsurprisingly ticket sales were phenomenal. When Fairydean Football Club decided to build a new stand to replace the old wooden one, financing through local lottery was not a problem.

Serendipitously, the club treasurer Jimmy Walker lived in nearby Gattonside, where his neighbour was Peter Womersley, who perhaps over a pint, got the commission. Womersley, working with engineers, Ove Arup, decided to push concrete construction to its limits. Work started with the demolition of the old stand in October 1963 and it was opened officially with a ‘glamour friendly’ with East Fife on 21 November 1964. It was delivered at a cost of just under £30,000 – about £600,000 in today’s money. Rowan Moore, the architectural critic with The Guardian, has described it as “a miraculous work of concrete origami, which for force of constructional imagination and for architectural intelligence per cubic metre is hard to beat”

The beautiful innovative sharply angular design is realised in smooth plastered reinforced concrete. The shape, including the two delightful conical ticket stalls, seems to echo the angular negative space created by the Eildon Hills, immediately opposite the stand. (The design almost led to the commission for a new stand for Chelsea Football Club. It is a great shame this didn’t come to be). Womersley and Arup and especially Tom Ridley, benefited enormously from each other’s skills and determination; both had an unyielding belief in making original design become a reality.

In 2013 Gala Fairydean stand was given category A status by Historic Environment Scotland. In 2018, however it was closed amid safety concerns. Recently this modernist classic and its many fans have had some wonderful news. After fifty odd years of ageing, damage and ‘clogged alterations’, a team of engineers, architects and surveyors – David Narro Associates, Reiach and Hall, Morham + Brotchie and Irons Foulner -have been appointed to carry out some much needed conservation and restoration work. Steve Wood, one of the directors at David Narro has described it as “one of the most important buildings in Scotland”. The original photographs, devoid of the jarring advertising logos, show the roof almost floating off the stand. I do hope this crucial feature is recovered.

High Sunderland (1956-1958) and the Klein Design Studio (1970), north of Selkirk

Bernat Klein, the noted textile designer, was to become one of Womersley’s closest friends and best clients. Klein’s work took him to Yorkshire, that other centre of textile manufacturing, where he and his wife spotted Womersley’s first building, Farnley Hey built in 1954 for Womersley’s brother. This chance encounter “so excited him on a visceral level that they had to know who designed it… and they knocked on the door”. A man of determination, Klein wrote to Womersley the very next week asking him if he would design a house on their plot five miles outside Selkirk. Womersley saw the future house as a timber framed pavilion comprised of two separate wings with two courtyards. It was constructed between 1956 and 1958, just a couple of years after the completion of Farnley Hey.

High Sunderland has, justifiably, received a great deal of attention in the last few years. Firstly, its sale through The Modern House estate agents by Bernat’s daughter Shelley Klein, where interested readers might seek further details and beautiful architectural photographs. Even more recently Shelley’s insightful and poignant memoir The See-Through House: My Father in Full Colour (2020) tells the story of High Sunderland from first hand experience. And its recent serialisation on Radio 4 will bring more people to Womersley’s architecture.

The house is a complete and delightful surprise. It is only glimpsed through thick trees atop a small hill on the winding road between Selkirk and Peebles; it’s easily missed. Going up the steep drive one is suddenly presented with a multicoloured and variously textured jewel that in terms of proportion and ambition could be straight out of the Case House Study project of 1950’s and 60’s America.

The coloured and mosaic wall panels outside are a delight, especially in the Scottish Borders, where the architecture can be dour. There is yellow, green, black and fawn. The house is contained within an area of only 34 x 13m, including walled garden and garage spaces, but seems Tardis-like. Inside everywhere seems bright due to the expansive glazing. Womersley designed the built-in furniture and with Klein created a tapestry of textures and finishes. Woods used include idigbo, maple, rosewood and walnut. Curtains and fabrics were designed and made in Klein’s own mills. The architect & founder of Archigram, Michael Webb said “A plain-sided glass box sitting on a hill could easily seem frail or banal; however the contrasts of solid and void, varnished boarding and full glazing, within the white frame, give the house strength and character”.

Mark Girouard, the architectural historian, in ‘An Outstanding Modern House’ an article written in 1960 for Country Life wrote “One of the most interesting aspects of the design is that this rigid and complex piece of rectangular geometry, carried out in crisp brown and white wood and glittering glass, acts as an exhilarating foil to the curves and spacious greenness of the Border landscape, which comes straight up to the house with no intervening garden- a standing rebuke to the local councils who turn such designs down on the grounds that they will not harmonise with the surrounding countryside…. High Sunderland… is undoubtedly one of the best private houses designed in this country since WW2”.

Simply put, this house is revelatory. But again, with age, it needed expensive repairs to the flat roof (leaks were common). I believe that the new owners of High Sunderland are currently investing a great deal of time and care in the restoration of this treasure, one of Womersley’s most beautiful dwelling houses and still one of the best houses in Scotland.

Incredibly, and to our shame, another Womersley-designed treasure, just a few yards away from High Sunderland, is rotting away. The Design Studio (designed 1969-72, built 1972) again built for Klein to design and showcase his fabrics is an “exceptional composition in concrete, brick and glass, which appears to grow out of the ground and float among the trees” (Cruft, Dunbar & Fawcett, Buildings of Scotland, Borders 2006). It won an RIBA award for design and exemplary use and combination of concrete, brick, steel and glass. The small but incredibly powerful building marries Womersley’s horizontal pavilion houses of the 1950’s with the sculptural ‘brutalist’ concrete works of the Fairydean football stand and his nearby boiler house at Dingleton. A bit of his beloved Fallingwater with almost an Eastern influenced architecture perhaps; it’s unlike anything else in Scotland. And almost nothing has been done to preserve it (or even to convert it into a dwelling house, as was intended) for almost twenty years. A pressure group, Preserving Womersley, has been set up to help save the building and see it restored and preserved.

Architect Neil Gillespie has suggested that we as a nation might actually be happier with modernist masterpieces such as St Peter’s Seminary and Womersley’s Klein studio in ruins, part of a phenomenon known as ‘Ruinenlust’. The 18th century German compound word, Ruinenlust describes the curious psychopathology of being drawn to that which we most fear; ruination and decay. He asks the salient question “How can this feeling for a modernism that was based on social improvement be acted on in a currently re-politicised Scotland?” Ruins are indeed easier for us to deal with. We can blame decay and decline on the vicissitudes of time; it’s someone else’s fault, this neglect. The problem of care and maintenance is gone. Perhaps we should just invite artist Rachel Whiteread (whose works remind us that ruins are a product of two opposing forces, persistence and decay) to come and make a concrete cast of the Klein studio, preserving its proportions, materiality and poetry in a pure sculpture of concrete? Then we could set this life size sculpture safely in one of our major cities museums, or a sculpture park? That way we’d still have the ‘art’, the relic, but not the problems.

I’m being deliberately provocative of course. However if nothing is done – and soon – about the Klein studio it will be lost forever. The authorities step in quickly to take control in the case of other types of neglect, why not for invaluable works of our architectural culture?

Womersley believed in the three Vitruvian principles of architecture (firmitas, utilitas, venustas) translated by Sir Henry Wooton as “firmness, commodity and delight”, but insisted the foremost amongst these should be ‘delight’. Womersley did not have a house style in the way that stararchitects do today. Each building project has its own look and feel. Not only did he make a large number of different buildings (football stand, social housing, office buildings, private houses, boilerhouses, health buildings and artist studio) but also they are mainly concentrated in a tiny area – a few miles in diameter – around his practice and home near Melrose. It might be suggested that being off the beaten track in the self-contained Borders allowed Womersley to give himself permission to follow his own ideas and philosophy. This is an area long noted for its independence in culture and much else.

Home, again

When we moved back to Scotland to settle in Hawick we decided to build a modern minimal house. Almost naturally, we decided to use the homes of Peter Womersley for clues and cues. Hawick is almost alone amongst Borders towns in having no Womersley buildings; this is surprising since it was the biggest and wealthiest town in the Borders. We visited two of his houses in Gattonside and High Sunderland and his Klein studio and decided our own new home should have as large windows and as much light as we could afford. Womersley disliked interior doors so our house is fairly open plan too. Our larch cladding gives a uniform look in the way that Womersley’s ‘brutalist’ concrete buildings do, but the now silvered larch provides a softer look, an aesthetic overlap with the adjacent mature trees. We wanted surprising splashes of bright ‘modernist’

Brian Robertson is the curator of Zembla, an occasional gallery for contemporary art which opened in 2016 & is based in a ‘Modernist’ new build house in the Scottish Borders. It’s long been Robertson’s wish to exhibit work by contemporary artists which take as their starting point Womersley’s buildings. He is currently working with 12 artists on such an exhibition which will take place in 2021. @zemblagallery.